Partly this was, in the seventies and early eighties, a function of their very otherness as Germans working in a cultural form still very much defined by an Anglo-American identity – Trans-Europe Express was, the New York DJ and rapper Afrika Bambaataa recalled, quite simply ‘one of the weirdest records I ever heard’ – an otherness which is not only foregrounded by Radio On, but which was deftly mobilised by Hütter and Schneider themselves in their self-presentation throughout the period. This sense of Kraftwerk as an embodiment, musically and existentially, of the very image and idea of the new is, of course, one which resonates not only through their extraordinary influence on the ‘electronic reality’ of the music emerging from the industrial towns of Manchester and Sheffield around the same time as Petit’s film, but more strikingly, and far more peculiarly, in the black metropolises of the South Bronx, Miami and Detroit. Before setting out to drive from London to Bristol, through an England shadowed by terrorism and the war in Ireland, the film’s protagonist is introduced opening a package from his dead brother containing three tape cassettes of the band’s 1970s albums, Radio-activity (1975), Trans-Europe Express (1977) and The Man-Machine (1978): sounds and images of a modernity starkly at odds, the film suggests, with the nostalgia of the pub rock which makes up the bulk of the British part of the film’s soundtrack. And certainly their music has an unusually prominent role in the film. Petit has claimed in interviews that he became a music journalist solely with the intent of meeting Kraftwerk. The words come from Kraftwerk, the group which Florian Schneider founded with Ralf Hütter in Düsseldorf in 1970 – a fitting reference, given Radio On’s larger fixation on German music and cinema as an alternative to the hegemony of Hollywood’s dreamworlds and an increasingly desiccated Anglo-American rock still in thrall to the mythos of ‘the sixties’. All change in society passes through a sympathetic collaboration with tape recorders, synthesisers and telephones.

We are the link between the ‘20s and the ‘80s. We are the children of Fritz Lang and Werner von Braun. Structured, like most of Radio On, as much by its late 1970s’ musical soundtrack – in this case the English-German version of David Bowie’s six-minute Heroes/Helden recorded at Hansa Studios in Berlin – as by any conventional narrative drive, the opening shot lingers, briefly, on a handwritten sign pinned to a bedroom wall:

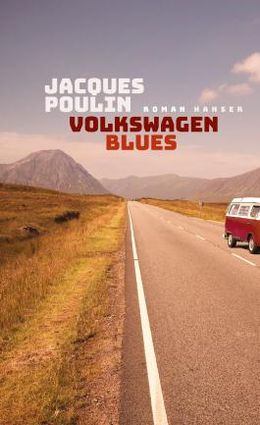

VOLKSWAGEN BLUES COLONISATION MOVIE

A singular attempt to graft a Wenders-inspired German version of the US road movie onto a bleak, run-down, black and white English landscape during the dog days of the Callaghan government, the film opens with a long tracking shot that creeps slowly around a dimly-lit flat in Bristol, before coming to rest on the feet of a suicide in his bath. Not long after the death of Florian Schneider was announced in May of this year, 1 I re-watched the 1979 film Radio On, directed by Chris Petit, and co-produced by Wim Wenders.

‘There is no beginning and no end in music … Some people want it to end but it goes on’

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)